ON February 5, 1805, stormy weather was battering the Dorset coast.

Among those struggling to navigate the rough seas was the Earl of Abergavenny – an East India Company ship captained by John Wordsworth, brother of renowned Romantic poet, William.

At some point that day, due to human error amid the stormy conditions, the 1,460-ton vessel struck the Shambles sandbank, and sank around 1.5 miles off Weymouth, costing 250 lives.

Alongside the human tragedy was a financial one for the East India Company – with some 62 chests of silver dollars also lost in the sinking. The haul – estimated to be worth around £7.5 million today – has never been found.

Now, the wreckage of the Earl of Abergavenny has been scheduled by the Department for Culture, Media and Sport (DCMS) on the advice of Historic England.

The designation means divers can dive the wreck but must leave its contents in situ.

The cargo ship launched in 1796 in Northfleet, Kent, and is rare as one of only 36 ships of 1,460 tons that formed a special class of the company’s merchant fleet.

It was an early example of the changing technologies in ship building of the time, incorporating the use of iron in its construction.

Together with other East India Company vessels, it contributed to the growth of western economies during the 17th to 19th centuries by changing the focus of Britain’s trading operations from Indian textiles to China tea.

The Wordsworth family had a close association with the East India Company and John Wordsworth embarked on a life at sea to help support brother William’s writing career.

He captained two successful voyages on the Earl of Abergavenny to China but lost his life off the Dorset coast on his fifth trading voyage from Portsmouth to Bengal and China.

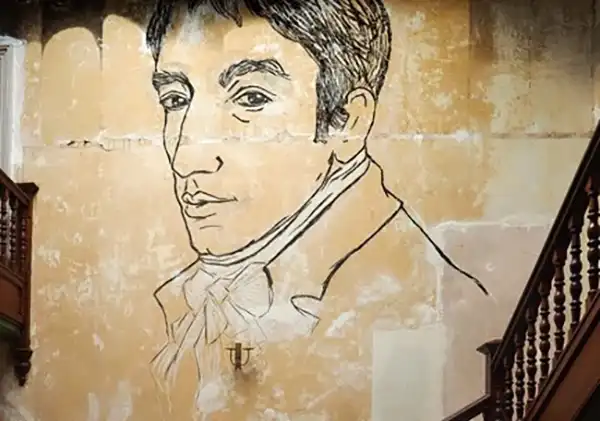

A portrait of William Wordsworth in the Staircase Hall at Allan Bank and Grasmere, Cumbria. Picture: National Trust

The ship lies at a depth of 16 metres on the seabed, and there are substantial structural remains of the hull measuring approximately 50 metres by 10 metres.

It includes planking, frames, and fixtures and fittings such as a chain pump (a type of water pump) and iron knees, which are brackets in the structure of a wooden ship. The wreck has not been fully excavated, so it still has many stories to tell.

“This wreck has an evocative story to tell about the life and sorrow of one of our most renowned poets, William Wordsworth,” said Duncan Wilson, chief executive of Historic England.

“But it also has an important place in this country’s shared maritime history and how the East India Company’s fleet made its impact across so much of the world.

“Its protection is testament to the dedication and hard work of Chelmsford Underwater Archaeological Unit, Weymouth LUNAR Society and Portland Museum and their volunteers.

“Their efforts will help us all learn more about this vessel and its place in our shared past.”

The grief William was experiencing following the loss of his brother is evident in Elegiac Stanzas, where his previous belief that nature was good and kind, is rejected.

After the loss of John, William’s work turned and became more reflective and bleak.

The Portland Museum, in Portland, houses a collection of artefacts from the wreck site when it was excavated in the 1980s, including a cufflink believed to have belonged to Captain John Wordsworth.

A cufflink believed to have belonged to John Wordsworth, left, and lead cloth seals recovered from the shipwreck. Pictures: Portland Museum Trust

The museum was awarded funding from the National Lottery Heritage Fund in November 2021 to launch the Diving into the Digital Archives of the Earl of Abergavenny project – a digital volunteering initiative aimed at breaking down barriers to heritage.

As part of the project, which continues today, the Museum’s volunteers produce 3D models of the artefacts from the Earl of Abergavenny and make them publicly available.

David Carter, trustee of Portland Museum, said: “I’m delighted the Earl of Abergavenny has been granted protection. It played an important part in British history.

“Being involved in the underwater excavations from the 1980s and seeing the artefacts conserved and finding a home at the Portland Museum has been a major achievement.

“I’m proud of our volunteer team who make hundreds of finds from the wreck site digitally available and accessible to all.”

Leave a Reply